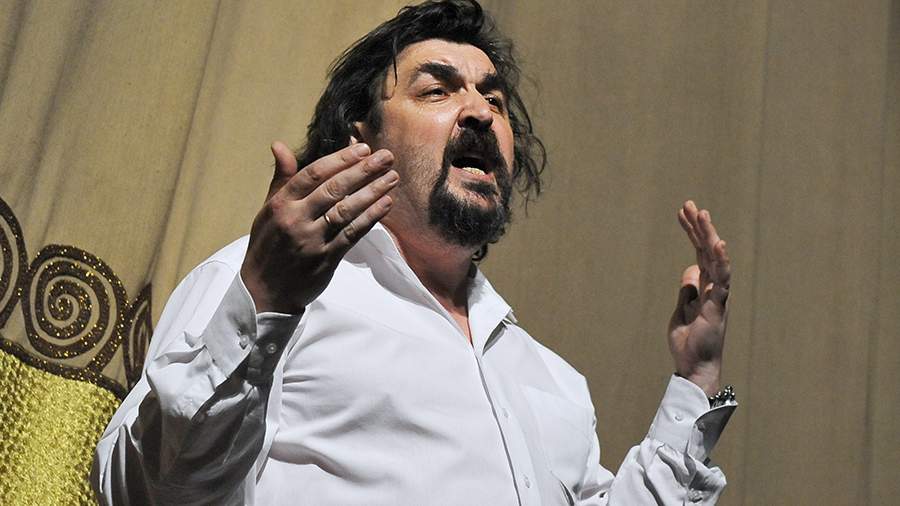

Igor Zolotovitskiy

June 18, 1961 – January 14, 2026

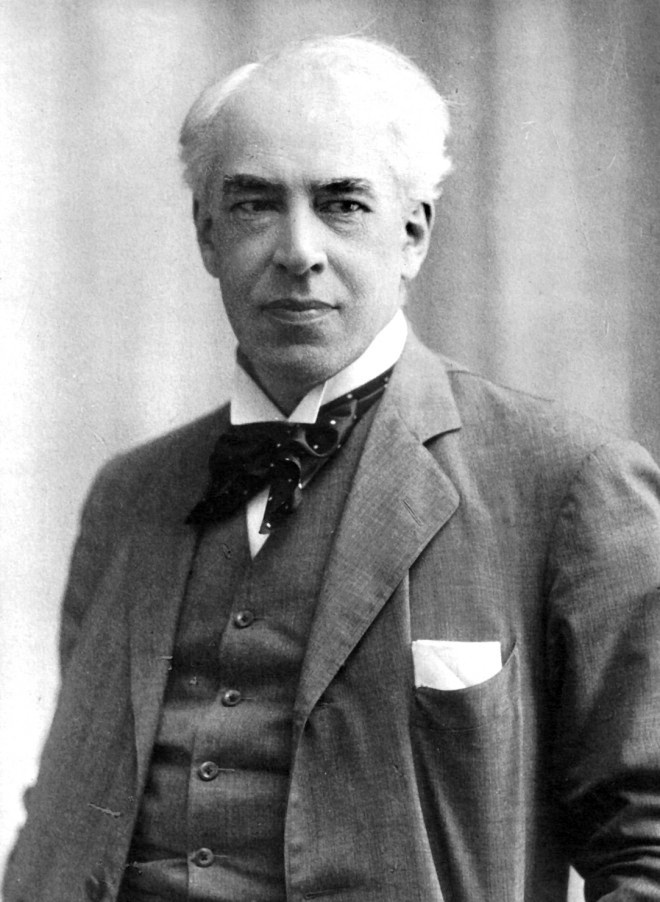

Konstantin Sergeyevich Stanislavsky | 1863 – 1938

Opera San José : Can you describe your introduction to the Stanislavsky tradition and what initially drew you to this lineage of Russian theater?

Shawna Lucey: As a teenager, I fell deeply in love with Chekhov’s plays and the story of the Moscow Art Theatre. I was captivated not only by the emotional complexity of his characters, but by the idea that an entire institution had been built around the pursuit of truth in performance. Even at a young age, I sensed that something essential was happening in that tradition—something far deeper than technique alone.

That instinct led me to complete a post-baccalaureate semester at MXAT, where I met Igor Zolotovitsky and his colleague and closest collaborator, Sergei Zemtsov. In the United States, Stanislavsky is often understood through his influence on figures such as Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, Elia Kazan, and Marlon Brando. While I deeply respect that lineage, I felt increasingly dissatisfied with the fragmented way acting was sometimes taught in my university training

I knew, intuitively, that if I did not go to Russia and study at the source, I would always feel that something fundamental was missing. When I finally arrived in Moscow—first for that initial semester and later to study Russian and earn my MFA at the Schukin School—the experience surpassed everything I had imagined. It was immersive, demanding, and transformative. That training continues to shape how I think, feel, and work as an artist every single day.

OSJ: Igor Zolotovitskiy was a direct inheritor of the Stanislavsky school—what did it mean to study under someone so closely connected to that legacy?

SL: Igor and Sergei were directly connected to the living Stanislavsky lineage, having studied with students of Stanislavsky himself. They were not simply transmitting a historical method—they were actively evolving it, testing it, and refining it in response to contemporary artistic realities.

What struck me immediately was the seriousness with which they approached our development. We arrived as young, inexperienced students from around the world, yet they treated us as artists in formation, capable of profound work. They never simplified the training for our comfort. Instead, they demanded that we grow into it.

I had never experienced that level of respect and expectation before. It was both humbling and empowering. When I saw them perform—often before I spoke Russian—and realized that I was watching some of the finest actors I had ever encountered, I felt an overwhelming sense of gratitude. To learn from artists of that caliber was a rare privilege.

OSJ: How did Zolotovitskiy bring Stanislavsky’s ideas to life in the studio or rehearsal room, beyond theory or text?

SL: Igor Yakovlevich was a magnetic presence. He was larger than life—passionate, demanding, funny, and deeply humane. In those days, he often taught with a cigarette in hand, embodying a kind of old-world theatrical charisma that was inseparable from his artistic rigor.

Our training followed a carefully structured progression of increasingly complex exercises. Each day, we presented etudes—short scenes based on precise dramatic tasks. These were then examined rigorously, both by our teachers and our peers. Nothing was superficial. Every choice had to be justified.

The program itself was extraordinarily demanding. We studied ballet, the Droznin movement technique, Michael Chekhov’s method, Russian theatre history, voice, and acting. In the evenings, we attended performances almost every night—plays, opera, ballet—constantly observing how great artists worked in practice.

Through this relentless schedule, Igor and Sergei taught us that artistry requires total commitment: physical stamina, intellectual curiosity, and spiritual depth. They modeled the life of the artist in everything they did.

OSJ: Stanislavsky emphasized psychological truth and the inner life of a character. How did this training shape your understanding of emotional honesty onstage?

SL: Stanislavsky’s pursuit of “living truth” was never sentimental or vague. It was rigorous, methodical, and grounded in deep respect for human psychology. His writings make clear that emotional authenticity cannot be forced—it must be cultivated.

He emphasized creating the right conditions for creativity: safety, discipline, curiosity, and preparation. Inspiration cannot be commanded, but it can be invited.

That meant exhaustive research, careful reading, studying historical and social contexts, observing real people, imagining emotional histories, and returning again and again to the text. Russian literature, in this sense, became a lifelong education in empathy.

As a director, I now draw on this holistic approach. My goal is always to create an environment in which singers feel supported enough to take risks and grounded enough to explore the deepest emotional truths of their characters.

OSJ: What distinguished Zolotovitskiy as a mentor—not only as a teacher of technique, but as someone shaping the whole artist?

SL: Igor Yakovlevich was a working artist in every sense. While teaching, he was also performing, directing, and starring in major theatrical and film productions. His artistic life was fully integrated—there was no separation between practice and pedagogy.

In Russia, teaching theatre is considered a sacred responsibility. It is entrusted only to artists of the highest caliber. Igor embodied this ideal completely. His eventual appointment as head of the Moscow Art Theatre School reflected both his artistic stature and his moral authority.

His courage was equally remarkable. By publicly opposing the war and defending student protesters, he risked his career and safety. He used his influence not for self-protection, but for ethical leadership.

Like Stanislavsky before him, he believed that artists must serve truth above comfort. His example continues to inspire me.

OSJ: Is there a specific exercise, phrase, or moment from your time with Zolotovitskiy that continues to guide your artistic choices today?

SL: Our schedule was relentless. We studied with Igor and Sergei six days a week, for two and a half hours a day, for years. Every day, we presented work.

Feedback was uncompromising. They never offered empty praise. If something failed, they said so plainly and then guided us in understanding why. Failure was treated as part of learning, not something to be avoided.

On rare occasions, they would say, “Ochen tochna”—“Very precise.” That was the highest compliment. It meant the work was specific, truthful, and alive.

Those words still echo in my mind whenever I approach a new project.

OSJ: How has your grounding in the Stanislavsky tradition influenced your broader artistic leadership and vision at Opera San José?

SL: My years in Russia are foundational to my artistic worldview. They shaped not only how I direct and teach, but how I understand the social responsibility of artistic institutions.

In Moscow, theatre was not seen as entertainment alone—it was seen as a moral and cultural necessity. I once told a stranger that I was studying at MXAT, and he responded with profound respect: “To be an actor is to be a more evolved human, because you must understand so many lives.”

That philosophy guides my leadership. At Opera San José, my goal is to foster an environment where artists are respected, challenged, and supported. It is my honor to steward Irene’s extraordinary company and to help create work that matters.

Maria Natale as Santuzza | Cavalleria Rusticana | PC Chris Hardy

OSJ: Cavalleria Rusticana and Pagliacci are steeped in Verismo realism and raw human emotion. How do Stanislavsky’s principles help unlock the psychological depth of these works?

SL: Verismo demands absolute commitment to truth. There is no surface-level way to approach these works.

We begin by immersing ourselves in the text and score, then constructing detailed psychological and social backstories for each character. We examine relationships, histories, and unspoken tensions.

From there, we carefully shape the dramatic stakes of every moment. Each choice must arise organically from the character’s inner life.

This structure allows singers to move beyond “performance” and into genuine presence—responding truthfully to Maestro Deutscher, the orchestra, and each other in real time.

OSJ: Both operas demand extreme emotional vulnerability from the performers. How do Igor Zolotovitskiy’s teachings inform the way you guide singers through that intensity in rehearsal?

SL: Emotional vulnerability cannot be commanded. It must be earned.

Rather than asking singers to “feel more,” we build a clear dramatic pathway. We define objectives, obstacles, and emotional stakes. We establish trust within the rehearsal room.

Through this process, artists gain the confidence to surrender to the work. This approach comes directly from Igor’s teaching and remains central to my practice.

OSJ: For audiences experiencing Cavalleria Rusticana & Pagliacci, what do you hope emerges when these operas are approached through a Stanislavsky-influenced lens of truth and intention?

Ben Gulley as Canio | Pagliacci | PC: Chris Hardy

SL: I hope audiences recognize that these operas speak directly to contemporary life. Though written more than a century ago, they explore themes that remain painfully relevant: betrayal, jealousy, passion, power, and intimate partner violence.

These are stories we still live with today.

When approached with honesty and care, and brought to life through Mascagni’s and Leoncavallo’s extraordinary music, they become immediate and urgent. With Maestro Deutscher and our remarkable cast and crew, these works are not museum pieces—they are living human documents.

My deepest hope is that audiences leave feeling both moved and awakened.